Thirty-six years ago, Moscow dispatched the Soviet army to Baku ostensibly to defend Armenians but in fact to crush Azerbaijan’s drive toward independence. In the years since, the details of that event have been forgotten as many of the witnesses to those events have passed from the scene. But the importance of that event has only grown, not only for Azerbaijan but also for Moscow as well as for all those who have sought or are seeking independence from the Imperial center. And because that is the case, what Moscow did and how Azerbaijanis responded must never be forgotten by those who seek to understand why Baku has reacted to recent Russian actions and why others are increasingly doing the same, given the moves and threatening language coming out of the Russian capital.

Thirty-six years ago this week, on Mikhail Gorbachev’s order, Soviet troops by land, sea, and air invaded the Azerbaijani capital of Baku, killing hundreds and enflaming ethnic hatreds, in an action the Soviet president, five years after the events, acknowledged was “the greatest mistake” of his political career. That event, known to this day as “Black January” in Baku, was the result of Azerbaijan’s drive to recover its independence and what many Azerbaijanis saw as Moscow’s tilt toward Armenia, a combination that the Soviet government skillfully used in terms of propaganda to cover what was an act of aggression against those it insisted were its own citizens.

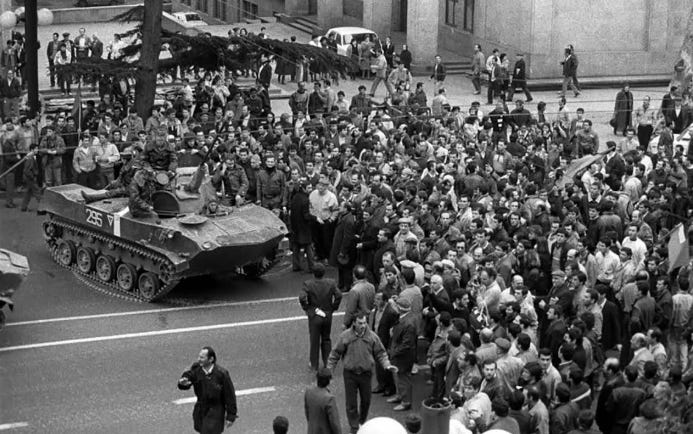

*The picture above was taken by Radio Free Europe of Russian forces occupying the Azerbaijani capital in January 1990

Gorbachev’s Crackdown

In the weeks before Gorbachev ordered the invasion, Azerbaijanis tore down the border fences dividing them from the much larger community of ethnic Azerbaijanis in Iran, and the Popular Front of Azerbaijan took over an increasing number of government offices around the republic. From Moscow’s perspective, the situation deteriorated on January 9 when the Supreme Soviet of the Armenian SSR voted to make Nagorno-Karabakh, the predominantly ethnically Armenian enclave in Azerbaijan, a de facto part of Armenia by including it within the Armenian SSR budget and allowing residents of Karabakh to vote in Armenian elections.

That outraged many Azerbaijanis, but they were also furious that Moscow failed to respond to the Armenian action. As a result, ever more Azerbaijanis then called for complete independence from the USSR and prompted the Azerbaijani Popular Front to set up committees for the defense of the nation. Officials in Baku were quite obviously losing control of the situation, and they directed the 12,000 troops of the republic’s Interior Ministry to stay in their barracks lest their appearance spark violence in the city. That quickly led to a breakdown in public order in parts of Azerbaijan and to attacks on Armenians, many of whom appealed to the Soviet government to help them leave. In response, the Azerbaijan Popular Front took control in many regions of the republic, and on January 18, it called on residents of Baku to block the main access routes into the Azerbaijani capital to block any Soviet forces that might be sent against them, and its activists surrounded Soviet interior force barracks there as well.

These developments led the Soviet officials on the ground to pull back to the outskirts of the city where they established a new command post to direct the Soviet response. That response was not long in coming. On January 19, Gorbachev signed a decree calling for the introduction of forces to restore order, block the actions of the People’s Front, and prevent anti-Armenian pogroms. Almost immediately, an estimated 26,000 Soviet troops entered the Azerbaijani capital. To justify their acts of violence, which claimed at least 100 lives and perhaps as many as 300, Moscow propagandists claimed that Azerbaijanis had fired on them. But a subsequent investigation by a Russian human rights group found no evidence of that.

Moscow worked hard to block information about what was going on from reaching the West or even reaching the Azerbaijanis. It blocked power to Azerbaijani state radio and television and banned all Azerbaijani print media. As a result, the main source of news, as the violence continued, became the Azerbaijani Service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Soviet forces occupied the city, but they did not break the Azerbaijanis’ drive for independence. Hundreds of Azerbaijanis turned in their communist party cards, and on January 22, after the Soviet violence had died down, the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan SSR met and condemned the actions of the Soviet forces.

The events in Baku quickly echoed throughout the USSR, prompting the formation of self-defense units in Tajikistan and encouraging national movements in Ukraine, Georgia, and the three Baltic states. And while Black January did not and still does not attract as much attention in the West as the far less murderous Soviet attacks elsewhere in Lithuania and Latvia, it is increasingly recognized that the events in Baku in 1990 triggered the final delegitimization of the USSR and thus played a central role in the demise of that country the following year.

Not surprisingly, the Azerbaijanis have never forgotten Black January. The holiest of holies in Baku is the Alley of Martyrs – in Azeri, Şəhidlər Xiyabanı – a cemetery and memorial to those killed by the Soviets during the 1990 events as well as during the First Nagorno-Karabakh war. The Azerbaijani government invariably takes important foreign visitors to this site, and Azerbaijanis themselves make pilgrimages to it, leaving flowers and other mementos to this day. That, as well as statements by senior Azerbaijani officials and commentators, has kept Black January very much at the center of the Azerbaijani understanding of the world, and especially about Baku’s relations with Moscow. Indeed, without this background, it is impossible to fully understand why Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and his government have taken such a tough line on more recent Russian outrages including the shooting down of a civilian Azerbaijani airliner in December 2024 and attacks on ethnic Azerbaijanis in Russian cities without reference to Black January – even when those events do not take place on the round anniversaries that the Azerbaijani government marks.

The Continuing Impact of Black January Beyond Azerbaijan

But even more important, perhaps, is the growing impact the image of Black January has had in recent years on nations that have not yet achieved their independence from Moscow. The clearest case of this is the way in which Bashkir activists responded to the Putin regime’s moves against them in 2023 and 2024 by calling them a new Black January. Ever more non-Russians believe that what Moscow did in Baku so long ago represents Russia’s inevitable alternative when faced with serious challenges, something that has intimidated many but that has led even more to recognize that when Moscow does use such indiscriminate force, that will backfire on the center and speed the further demise of the Russian imperial state.

*Russian propagandist Vladimir Solovyov

That sense has been heightened as a result of a statement made earlier this month by Kremlin propagandist Vladimir Solovyov, perhaps Moscow’s most prominent pro-Putin and pro-war television personality. He said that Moscow should launch “special military operations” like the one it is already carrying out in Ukraine against Central Asian and Caucasian countries if they do not do what Moscow demands. Solovyov further declared that what happens in “our Asia” and Armenia – in this diatribe, he did not mention Azerbaijan -- is far more important to Moscow than what happens in Venezuela, that international law is dead, that Russia should not care about the reaction of European countries, and that it should even expand its efforts to defeat Ukraine and bring Ukraine to heal.

Outlook

Not surprisingly, Solovyov’s words have sparked outrage in these countries and prompted their governments to raise the issue with Moscow, which sought to calm the situation by suggesting Solovyov’s words were only his “personal opinion.” Other analysts have suggested that the commentator’s words were his response to what the US had done in Venezuela and an assertion that Russia has the right to pursue similar steps in Moscow’s backyard. But others have pointed out that Solovyov is close to the Kremlin, hardly an independent actor, and that his threats are likely designed to intimidate non-Russians and prepare Russians for future “special operations” in Central Asia and Armenia, which provoked outrage in both Tashkent and Yerevan.

However that may be, what Solovyov has said is already generating a backlash, further deepening the divide between Russia and its neighbors and making it less likely that Moscow will be able to get its way with them however the war in Ukraine turns out, yet another way that the events of January 1990 in Baku continue to grow in importance even if many have forgotten the details of Gorbachev’s actions in Black January.

Thank you for your support! Please remember that The Saratoga Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization. Your donations are fully tax-deductible. If you seek to support The Saratoga Foundation, you can make a donation by clicking on the PayPal link below! Alternatively, you can also choose to subscribe on our website to support our work.

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=XFCZDX6YVTVKA

Thanks for reading! This post is public, so feel free to share it.