China Shuns Russian Plans for Grain-OPEC to Prioritize Infrastructure Investment in Jewish Autonomous Oblast in Russian Far East

by Sergey Sukhankin

On October 17, 2023 Russia and China signed a trade agreement hailed as the “deal of the century”. The agreement aimed to end the decades-long stalemate in the Sino-Russian grain trade, revitalization of the Russian Far East as well as foster closer economic-political ties between Beijing and Moscow as part of China’s broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Yet nearly three years after the agreement was formally signed, the results have been underwhelming for Moscow. Publicly available data reveals that Chinese imports of Russian wheat—the key commodity Russia aimed to export—plummeted after an initial period of growth. Exports of other grains also experienced a significant decline. This trend is particularly puzzling given that all contractual terms had been agreed upon: China pledged to purchase 70 million tons of grain over 12 years, worth a cumulative $26.5 billion. In addition, logistical solutions—such as the full-cycle grain railway terminal in Zabaykalsk situated near the Chinese border—were established by Moscow for the purpose of facilitating the rapid transport of Russian grain to China. However, after securing access to a cheap and abundant grain source, China appears to have put its original grain plans with Moscow on hold.

Beijing Fails to Embrace Moscow’s Plans for Grain-OPEC

Within Russia, the signing of the grain deal with China was celebrated as a clear-cut economic and political victory — yet another sign of the country’s resilience to Western sanctions. Russian officials and analysts viewed the deal’s anticipated benefits as follows:

First, the agreement was seen as a key enabler of Russian ambitions to expand its influence within non-Western platforms and organizations. Since the end of 2019 — when Alexey Gordeyev, a top-ranking Russian official, proposed that Russia, the European Union (EU), the U.S., Canada, and Argentina unite to form a “grain OPEC” — Moscow has sought to weaponize the use of grain as a geopolitical instrument. Following February 2022, Russia’s political leadership abandoned the notion of cooperating with the West and its allies, pivoting instead to leveraging grain as a tool to bolster BRICS and enhance its standing within the group. In 2024, for instance, President Vladimir Putin endorsed the establishment of a “BRICS grain exchange” aimed at challenging the U.S.-dominated global agricultural trade system and, potentially, weakening the U.S. dollar as the world’s global reserve currency.

Second, the deal with China was (and still is) viewed in Russia as a means to economically revitalize its Far Eastern grain-producing regions, which currently account for 14 percent of the country’s total grain output. However, as noted by Russian Minister of Agriculture, Oksana Lut, the grain-rich Far East —whose production potential is expected to grow and possibly generate a surplus of 12 million tons—lacks viable export alternatives beyond China and the broader Indo-Pacific region. Moreover, it is economically unviable for Moscow to subsidize the transport of Siberian grain to ports on the Black Sea and the Baltic.

Third, the agreement was also seen as a strategic move to sideline Ukraine as Russia’s main competitor in the Chinese grain market. Russian experts and officials complained that during the “grain deal” period (August 2022 – July 2023), Ukraine emerged as China’s primary grain supplier, while Russia’s share declined significantly. Through both military and political means, Russia hoped to supplant Ukraine as China’s leading provider of wheat and other agricultural products.

Fourth, aware of the risks and challenges associated with overdependence on a single buyer (China), the Kremlin hoped to use the grain deal with Beijing as a way to access additional—and alternative—channels for exporting Siberian grain to other actors in the Indo-Pacific region. For example, Russian experts described the deal as the acquisition of a kind of “Chinese channel” that would enable Russia to showcase its grain potential to the rest of Asia and significantly boost exports throughout the Pacific. However, these ambitious and far-reaching plans were met with China’s evasive and difficult-to-interpret response.

China Opts for Far Eastern Integration

At first glance, one might assume that Chinese restrictions on Russian grain imports stems from a long-term strategy to avoid reliance on a single supplier—a pattern most evident in the hydrocarbon sector, where Beijing seeks to limit its energy dependence on Moscow. But according to top Russian grain officials, China’s approach is politically motivated. For instance, the President of the Russian Grain Union (RGU), Arkadi Zlochevsky, lamented that it is the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—acting under the pretext of artificially constructed (and anti-Russian) phytosanitary regulations—that has effectively banned Russian grain imports. As a result, he noted, Russian exports have stalled, and infrastructure specifically developed to boost Sino-Russian grain is not functioning. While Zlochevsky did not offer a clear explanation for China’s behavior, one of his remarks stands out: although China generally ignores Russian wheat and reduces imports of other grains, it allows—and even encourages—grain imports from Russian regions near the Sino-Russian border. Though seemingly contradictory, this observation may be better understood in light of China’s broader activities in the Russian Far East.

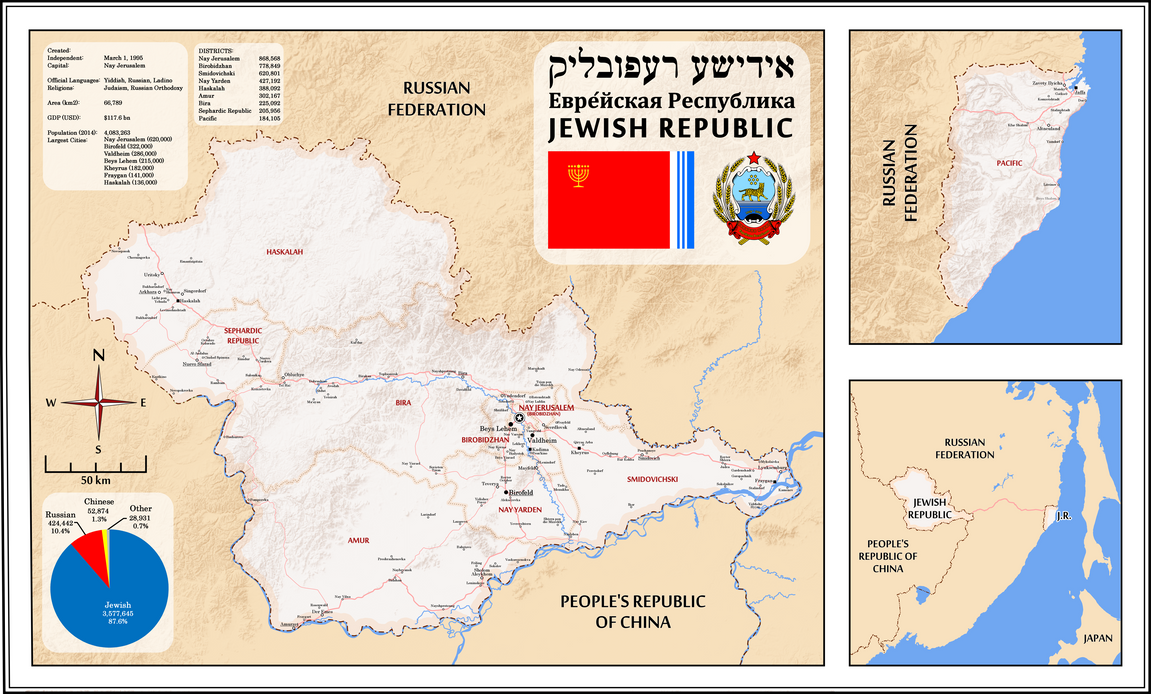

An analysis of fragmented reports concerning China’s post-February 2022 activities in the Far East reveals a striking trend: China has rapidly and proactively pursued a “fusion” of its border regions with adjacent Russian territories. A glaring example of this trend is the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO)[1]—Russia’s only autonomous oblast in the Far East. Rich in critical natural resources—Chinese inroads into the JAO clearly exemplifies this developmental trend, which is evident in three specific ways.

First, China is physically connecting its northeastern border areas in Manchuria with the JAO through a network of infrastructure projects focusing on regional transportation. For instance, the Chinese side has recently expressed its interest in creating and financing a transportation hub which will include, among others, construction of a bridge across the Amur River connecting China’s vastly populated border areas (more than 200 million people) with the sparsely populated JAO, which as of 2025 had a population of only 144,428. The official purpose of the bridge and related infrastructure is explained by the growing need for transportation of, among other things, grain and agricultural products.

Second, China acts proactively by offering to finance construction of factories and other production facilities on the territory of the JAO. For instance, the Chinese side has voiced its interest in financing the construction of a large agriculture-production facility (50 hectares) that would specialize in the production of and transportation of livestock, corn, oils, starch, and other types of agricultural products including, locally produced grains and soybeans. In addition, Chinese investors are willing to build factories specializing in the production of agricultural machinery, snowmobiles and motor vehicles.

Third, another method used by Beijing are cultural-educational exchanges. Here there are two main elements in its strategy: language exchanges between Russian and Chinese schoolchildren (this initiative is likely to take off shortly), which aims to popularize Russian and Mandarin among youth living on both sides of the border. Given the overwhelming difference in population[2] between the two provinces, this initiative appears to be much like a one-sided initiative aimed at the popularization of Mandarin. On the other hand, the leadership of the JAO volunteered to host Chinese performing artists from Jiamusi (佳木斯) in cultural events in Birobidzhan (the capitol of the JAO), whereas the Chinese side proposed to expand this initiative and deepen this cultural exchange adding sporting events, education and tourism to the Birobidzhan and its partner city in China, Jiamusi as part of their nascent partnership. On the one hand, this border exchange follows the principles of regionalism. However, it is worthwhile to mention that for the Kremlin it was the fear of regionalism and strengthening cross-border ties that de-facto led to the demise of the EU-backed Euroregion initiative in the Baltic Sea (Kaliningrad) and the Arctic (Karelia) regions. By comparison, the regional cooperation between the JOA and the Chinese province of Heilongjiang (黑龙江)[3] is taking place in a much more independent manner than Russia’s approach toward its Western regions.

Thus, while Chinese grain imports from Russia are decreasing in general, economic, cultural and other forms of cooperation between China’s and Russian border regions in the Far East have experienced a notable upsurge since 2022.

Conclusion:

On the surface, the Russian side welcomes the exponential growth of cross-border cooperation between Russian and Chinese regions and will continue to temporarily overlook difficulties in the grain trade, given China’s signed commitment to the so-called “deal of the century.” But Russian experts are increasingly concerned about Chinese behavior and possible ulterior motives in the Far East. Prior to the outbreak of the full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war in 2022, such concerns were expressed more openly, while now Russians’ reservations are no longer publicly expressed. As early as 2017, for example, Russian sources reported that up to one-third of all the arable land in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO) was being cultivated by Chinese nationals—prompting some to note, with grim irony, that “there are many more Chinese [in the JAO] than Jews.”

High-ranking officials, such as Mikhail Shchapov—a lieutenant colonel in the Federal Security Service (FSB), and a deputy of the 7th and 8th State Dumas—went so far as to issue a public warning in the Russian newspaper Nezavisimaia Gazeta to this effect about threat posed by Chinese migration. He claimed that Chinese nationals were present in Siberia and the Far East in significant and largely undocumented numbers, stating that this situation “does not look like the right thing to do, either from a market development or from a food security perspective.”

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and Moscow’s growing dependence on China, such criticisms largely disappeared from the Russian public discourse. Nonetheless, a handful of post-2022 publications continued to raise questions about China’s long-term intentions in the Far East. One such article, titled “The Chinese Future of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast,” while generally supportive of foreign direct investment (FDI), expressed concern over the nature of China’s entry model and operational practices in the Far East.

The Nezavisimaia Gazeta emphasized that China appeared primarily interested in using the territory as a resource base. It warned that, once Chinese enterprises establish a stronger foothold, they may sidestep local taxation, import their own labor force, and displace local Russian workers—an approach entirely consistent with Chinese investment behavior in other parts of the world.

These trends suggest that China will continue to capitalize on Russia’s weakened position following its near-total break with the West because of the Ukraine war. Yet, to avoid provoking Moscow during this period of vulnerability—which could risk further destabilization or even partial internal fragmentation—Beijing appears to be pursuing a dual-track strategy. Publicly, it presents Russia as an equal partner, exemplified by high-profile agreements like the “deal of the century.” Privately, however, it follows the cautious principle of “crossing the river by feeling for the stones” (摸著石頭過河), gradually and quietly integrating its border regions with the Russian Far East. This approach is particularly evident in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.

Notes:

[1] The JAO is a federal subject of Russia in its Far Eastern region, bordering Khabarovsk Krai and Amur Oblast and China’s Heilongjiang province. The JAO was created by a Soviet official decree in 1928 and officially established in 1934. Some Russian experts believe that the idea of creation of the JAO was primarily related to the Soviet Union’s desire to “solve the Jewish question” by on the one hand, distancing its Jewish population from the European part of the USSR (de-facto continuation of the Russian Imperial policy of systemic anti-semitism and created the JAO as an agricultural enclave as part of the USSR in its effort to resolve this issue.

[2] As of 2020, the population of Heilongjiang was 31,8 million which is 220 times more than the population of the JAO.

[3] It is worth mentioning that the Chinese province borders Russia’s Zabaykalsky Krai, Khabarovsk Krai, Amur Oblast, the JAO, and Primorye.

Thank you for your support! Please remember that The Saratoga Foundation is a non profit 501(c)(3) organization. Your donations are fully tax-deductible. If you seek to support The Saratoga Foundation you can make a donation by clicking on the PayPal link below! Alternatively, you can also choose to subscribe on our website to support our work.

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=XFCZDX6YVTVKA