Kitaizatsiya: China in Russia, Newsletter, Issue No.3

BRIEFS

Russian Security Services Arrest 2nd Chinese Spy

On September 22, Russian intelligence services detained a foreign national identified as Chizhen, accused of espionage, according to records from Moscow’s Lefortovsky District Court. The case, according to Moscow Times was marked top secret, and provided no details about the charges or the suspect’s location, though a hearing was scheduled for September 25th. Upon conviction under Article 276 of the Russian Criminal Code, Chizhen faces 10 to 20 years in prison, or potentially life imprisonment for offenses involving large-scale damage or collaboration.

This is the second espionage case in Russia reported during the month of September. The first instance was reported on September 15, by the Russian newspaper Kommersant involving a Chinese national, following the earlier arrest of Wang Yu.Ch. on similar charges. The unprecedented twin arrests - back to back - have drawn attention to growing Russian uneasiness about Chinese intelligence activity within Russia. According to CSIS’s ChinaPower report, China has engaged in extensive espionage and cyberattacks targeting Russian defense industries, particularly aerospace technologies, and has repeatedly violated licensing agreements by copying Russian weapons systems such as the Su-27 fighter and S-300 missile system.

China Creates Grain Corridor Between Amur and Sea of Japan

On September 23, 2025, China launched its first cargo ship, Xiang Yue Su Hang, to navigate Russia’s inland waterways along the Lower Amur River — a milestone in expanding Sino-Russian transport cooperation. According to Russia’s Ministry of Transport, the ship began its route in Taicang, southern China, passed through the Sea of Japan to Vanino, and continued upriver to Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk, and China’s Fuyuan. The voyage, part of the joint “Northeast China–Russian Far East” intermodal transport corridor, aims to boost regional trade by moving technical fleet vessels to China and returning with grain cargo to southern Chinese ports.

To support this initiative, China is modernizing the deep-water port of Manjit in Fuyuan to handle container shipments within the “Jinliang” cross-border agricultural project, creating a so-called “grain corridor” between the Amur and the Sea of Japan. The development highlights Beijing’s growing logistical influence and Moscow’s increasing economic dependence on China. Last summer, it was reported that Russian-Chinese negotiations were underway regarding free passage for Chinese vessels through the Tumen River, which flows into the Sea of Japan.

Beijing has repeatedly sought passage from Moscow along the Tumen route, but until recently has encountered strong Russian resistance to this initiative. However, amid Russia’s growing economic dependence on China, the issue was resolved back in 2024 China’s favor. The Tumen river runs along the border between China and North Korea, and then along the border between Russia and the DPRK. It is located in areas that previously belonged to China until the mid-19th century. Currently, Chinese ships can only navigate the river as far as the village of Fangchuan and are unable to access the lower reaches—a 15-kilometer stretch that allows them to sail out to sea.

Putin’s Multi-Path ‘One Belt, One Route’ Corridor Plan Marks New Phase in Russian Sinicization

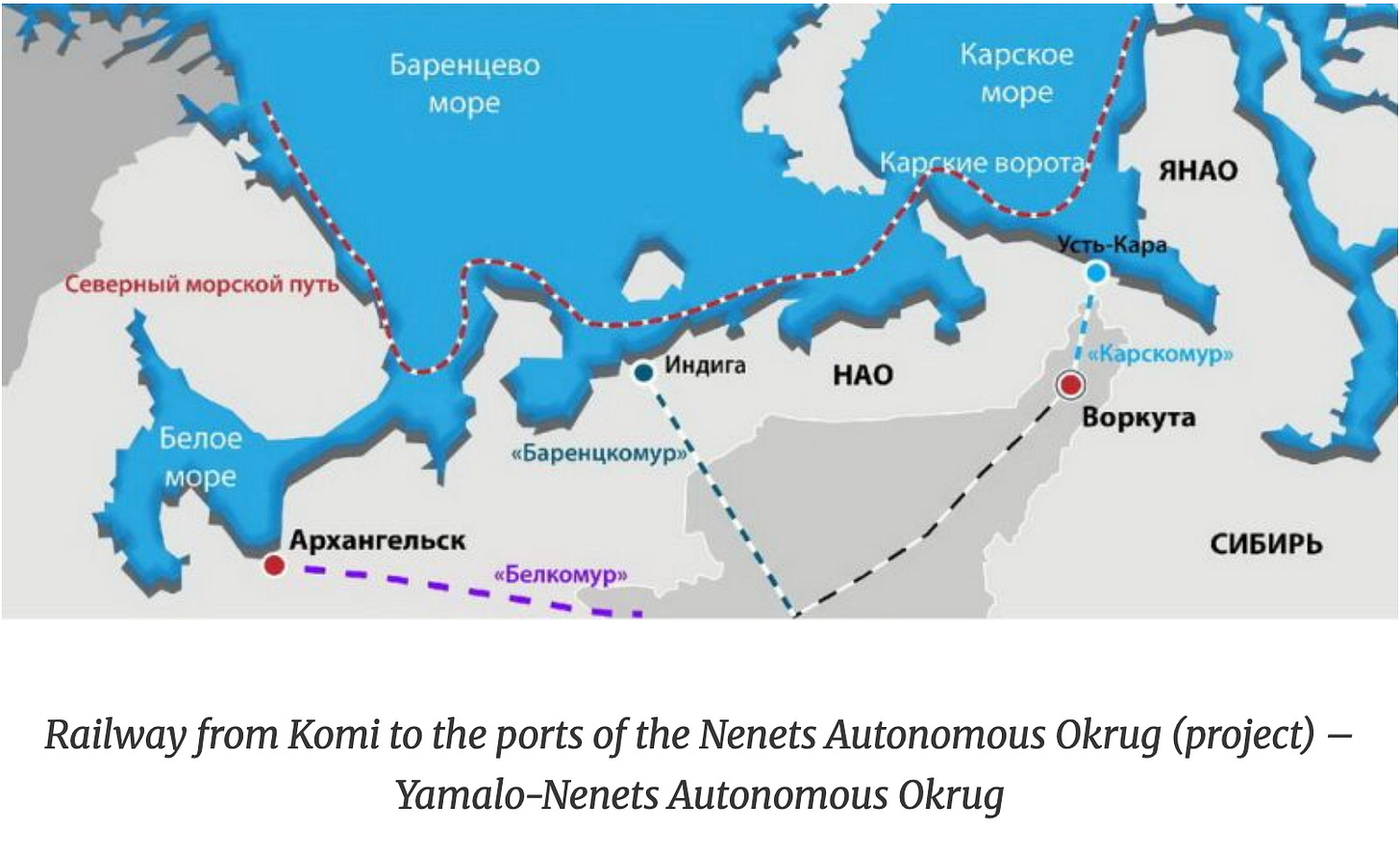

For most of his time in power, Putin has made the development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) with a single pathway his focus for the development of east-west trade, while over the same period, Chinese leaders have adopted their original “one belt, one road” approach (now known as the Belt and Road Initiative), to develop multiple pathways over land and sea to expand trade between Asia and Europe. In part, Putin’s approach up to now reflects the difficulties Moscow has faced in developing the kind of intermodal systems that multiple routes would require; and in part, it reflects the enormous difficulties for the Russian ruler in building rail lines and highways in the Russian North, where the melting of permafrost adds to the expense and difficulties of distance in doing so. But now, when the NSR has not lived up to expectations and when Russia and China are cooperating ever more closely, Putin is changing his approach and urging the adoption of what looks like a Russian analogue to what China has long been doing, clearly in the hope that Beijing will bail him out in this area.

In reporting the Kremlin leader’s words from last month, Moscow national security commentator Dmitry Nefyodov acknowledges that Putin specifically failed to use the Chinese term, limiting himself to rechristening the NSR the Trans-Arctic Corridor. But the analyst includes a reference to the Chinese “one belt, one road” approach in the title of his article and makes it clear that what Putin is now about is beyond any doubt a copy of what Beijing’s leaders have been doing in their pursuit of the development of east-west trade for some time.

According to Nefyodov, who provides numerous detailed maps showing the routes of these new “paths,” Putin plans to jump-start the use of the NSR by extending rail lines north from the Trans-Siberian and BAM railroads. This would allow shipments between Asia and Europe to use segments of the NSR, rather than being forced to rely on the sea route along its entire length — or avoid it altogether. The challenges of developing such a system are both numerous and large.

Not only would such a program require massive investment, something Putin clearly hopes the Chinese and perhaps others will supply, but it would necessitate Russia overcoming the problems it has suffered with the construction of rail lines in the North, something it has often failed at in the past, and in the handling of intermodal transit of cargo. The latter is especially difficult as shifting cargoes from trucks to trains to ships and from riverine ships to ocean-going vessels is not easy. Moscow has had extreme difficulties in overcoming them. As a result, Russian failures in this sector have reduced the overall speed of Russian routes, thus adding to their costs and reducing their attractiveness to potential users, particularly as Western sanctions have forced Moscow to lower its expectations by reducing the number of vessels it will build from 70 to 16 ice-class vessels to expand the Northern Sea Route.

Nefyodov describes these problems in great detail, and his tone suggests that this new Russian analogue to the Chinese approach is unlikely to work any better than the NSR has. Given that this year, the NSR is carrying less than half of the volume of trade Putin predicted for it as recently as two years ago, that may preclude both Chinese investment in the new rail lines and thus any chance that the multi-path trade corridor will ever be built. What that means, of course, is that perhaps the most important aspect of this new Moscow proposal is not that it will ever be built and achieve Putin’s goals, but that it reflects the Kremlin leader’s willingness to copy what the Chinese are doing and the readiness of Russian commentators to say what he is doing—something unimaginable only a few years ago. It is also a reflection of the increasing influence China is having on Russia and the willingness of Russians like Putin to swallow their pride and accept that Beijing, rather than Moscow, is the pathfinder on such issues.

But that psychological shift is the most important indication of the Kitaizatsiya (Sinicization) of Russia following Putin’s turn away from the West and toward China and Asia. It is a shift Russians may welcome in the abstract but may be outraged by when it comes down to specific steps—be they the purchase of Chinese cars rather than European ones, or the copying of Chinese state policies like Beijing’s original “one belt, one road” initiative rather than going it alone as the Kremlin has generally sought to do.

**NOTE: Photo above is the signing of a cooperation and collaboration agreement between the Government of Yakutia and the Union of Chinese Entrepreneurs in the Russian Federation signed during the 10th Eastern Economic Forum, attended by the head of the republic, Aisen Nikolaev, and the Union’s chairperson, Zhou Liqun.

Chinese Inroads Into Sakha

During the recent Eastern Economic Forum held in Vladivostok from September 3–6, 2025, the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) and the Union of Chinese Entrepreneurs in Russia (UCER) ) signed an agreement on cooperation and collaboration aimed at strengthening bilateral ties in trade, investment, logistics, and manufacturing. Local Sakha-based sources believe that this agreement will further enhance cooperation between China and the Republic — a partnership first launched in 2004, when Sakha signed an agreement with China’s Heilongjiang Province.

Since then, the scope of Sino-Sakha relations has expanded significantly: China has become one of the Republic’s top foreign trading partners, and 19 of Sakha’s municipalities have established “sworn brotherly” (pobratimy) relationships with 22 Chinese cities and counties – notably in Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces. Despite the apparent growth in bilateral trade and the seemingly positive trajectory of Sakha-China relations, China’s approach toward Yakutia since 2022 has been quite cautious — seeking to avoid major collaborative projects while switching its priorities toward soft power initiatives prioritizing engagement directly with local elites rather than with Moscow.

Chinese Economic Expansion Into Sakha

Chinese economic advancement in Sakha became evident even before the outbreak of the full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war in 2022. As early as 2021, local sources reported that China was steadily increasing its presence and had become one of Sakha’s key foreign trade partners. At that time, China’s share in Sakha’s foreign economic cooperation stood at 27.5 percent, reflecting the Republic’s growing dependence on Chinese trade. By 2024, this share had surged to over 45 percent, with Heilongjiang, Jiangxi, Jiangsu, Shandong, and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region emerging as Sakha’s principal trading partners.

The foundation of this bilateral trade remains straightforward—an import-export relationship in which Sakha serves primarily as a supplier of commodities and raw materials for China. However, Russia aims to expand cooperation beyond these traditional sectors. Currently, Sakha plays a key role in the export of Russian natural gas to China through the Power of Siberia pipeline, which has been operational since 2019. Under this project, Russia plans to supply Chinese customers with one trillion cubic meters (tcm) of natural gas over the next thirty years.

The role of Sakha is crucial both in terms of its resource base (the Chayanda field) and transportation based upon its geographical proximity to China. Moscow plans to utilize this interdependence by engaging Beijing in other strategic infrastructural projects such as the Dzhalinda–Mohe railway bridge across the Amur River, which the Russian side sees as an integral part of the Neryungri-Skovorodino-Dzhalinda-Mohe transport corridor project that is to play a critical role in the social economic development of Russia’s Far East and Baikal regions. While rumors about construction began circulating in 2022, and accelerated in 2023, China now appears to be cautiously approaching this issue. According to Russian officials, Moscow desperately needs this transportation route as a means to increase its exports of coal, LNG, lumber, iron ore due to its inability to cope with the rapidly growing East-bound traffic since February 2022. It reflects a clear inability of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Baikal–Amur Mainline (BAM) to cope with the growing volumes of cargo it is handling.

Analysis of Russian-language sources reveals an intriguing vision of how Moscow seeks to leverage Sakha—particularly its geography—in its efforts to deepen ties with China. According to Daryana Maximova, the Deputy Executive Director at the Secretariat of the Northern Forum international organization, “there is an agreement from the side of Moscow to transform Yakutia [Sakha] into a bridge between China and Russia.” Maximova emphasized that Russia is ready to satisfy Chinese interest in Sakha-based infrastructure by linking Chinese firms with the Northen Sea Route (NSR) through its territory. Based upon her statement, Russia is ready to grant China additional privileges in Sakha to turn it into a gateway to the Arctic.

Russia’s previous patterns of regionalism — exemplified by Kaliningrad and the Republic of Karelia, which formed part of the so-called Euro-regions (Evroregioni) before 2014 — are particularly telling. Cross-border cooperation in these areas was gradually strangled by Moscow’s obsession with combating alleged foreign malign influence. Against this backdrop, Russia’s apparent readiness to invite China into this distant and ethnically non-Russian territory is quite puzzling. The situation is further complicated by the fact that Moscow faces two key risks in doing so:

Risk #1: China’s White Elephant Projects in Sakha

Despite a growing volume of trade with Sakha—consisting primarily of commodity exports[1] —China has shown little enthusiasm for investing in strategic projects or committing significant financial resources to develop the Republic. Between 2006 and 2015, Russian sources enthusiastically touted Beijing’s “huge interest” in investment projects in Yakutia (Sakha) by Chinese firms and even at the state level. The reality, however, has proven to be quite different: most of the highly publicized ventures with expected Chinese participation turned out to be empty promises despite being hailed by the Russian media. For example, these include the following initiatives that never materialized:

· A major real estate developing project (400,000 square meters of apartment blocks) in the city of Yakutsk that was supposed to be carried out by a Chinese “Zhuoda Group,” but local authorities later dissolved the deal.

· A 2015 agreement between the Chinese side and authorities of the Sakha over the Tyrekhtyakh Creek tin deposit (the Ust-Yansky District) with estimated reserves about 68,000 tons.

· A 2015 bridge project through the Lena River signed with several Chinese companies, such as Hua Qin An Ju, Chzhundyan, Bo Chi Heilongjiang, Heilongjiang Main Company for Economic and Technological Development (translations are approximate given that the names come from Russian sources) and the China Development Bank.

· An investment project signed in 2018 to build a Hilton hotel in Yakutsk that was supposed to be carried out by China Overseas Holding Group Smarter City Fund Co. Ltd.

· A coke chemical plant in the Neryungri district, home to the Neryungri coal field, which is one of the largest coal-producing regions in Russia.

· An LNG-producing facility, which attracted interest from the Guangzhou-based Jovo Group, which would satisfy 30 percent of the province’s import of LNG. However, in 2019, following initial assessment, the company rejected an idea based on challenges with logistics and as claimed by Russian language sources, opted for imports from alternative projects in Southeast Asia.

Having listed some of the unfulfilled promises and expectations that the Russian side held regarding Chinese economic involvement in Sakha, it is important to note that these initiatives emerged during a period of relative economic and geopolitical stability. In light of current realities caused by the Ukraine war and international sanctions against Russia, the prospect of securing Chinese commitments to large and financially demanding projects in Sakha appear far less realistic than before. That said, despite these challenges, this does not imply that China has lost interest in Sakha or that Beijing’s engagement in the region is diminishing. On the contrary, China is building its influence inside Sakha by relying on soft power initiatives in order to strengthen its ties with Sakha.

Risk #2: China Turns to Soft Power

After the outbreak of the full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war in 2022, Chinese involvement with Sakha switched to a different track to deepen its ties to Sakha by expanding its cultural influence in the Far Eastern Republic in several directions.

First, it adopted identity-related narratives to promulgate its influence. In the post-2022 period the number of joint Sino-Sakha cultural events underscoring the “brotherly” nature of the bilateral relations with a tacit emphasis on “similarity” between the two groups increased dramatically. One example of such events is the “China – Yakutia: friendship of peoples” festival (the most recent one took place in 2024). While this and similar events could be viewed as a mere symbol of friendship and growing ties between the two parties, the undertone is quite clear, namely to demonstrate that the Yakuts and Chinese share a great deal of similarities. At this juncture, a series of very interesting publications appeared on the Chinese Sohu.com platform. While these publications cannot be taken as a reflection of Chinese strategy, yet their appearance in the Chinese information space deserve special attention because this media outlet is primarily designed for domestic consumption. Several consistent themes emerge from these publications which are summarized below:

· Sakha is the world’s second largest (after China) territory populated by “representatives of the “yellow race”[2] and that the majority of Yakutia’s 950,000 population are “yellow people,” who are connected with China through multiple historical ties.

· Sakha (Yakutia) is exceptionally endowed with natural resources but due to a variety of factors, this territory is likely to become depopulated in the foreseeable future.

· Sino-Sakhan ties must be developed in as broad categories as possible due to the fact that, aside from a mutually beneficial economic partnership, over time, this would grant Sakha more independence, i.e., from Russia.

At this juncture it is important to mention that after 2022, Russian-language sources reacted quite negatively – if not alarmingly - to these postings articles taken from the Chinese media space by claiming how Sakha (and other parts of the Far East) should one day return to China using the headline: “How China Views the Russian Federation Constituent Entity Sakha.”

*Chinese map of Siberia depicting administrative divisions during the Yuan Dynasty

Second, education and language. After 2022 Sakha-based sources indicate China expanded its use of Chinese educational and language-related programs and initiatives inside Yakutia. For instance, it was reported that Mandarin has become the primary foreign language of instruction being offered to students in an estimated 33 schools. This number appears to be particularly impressive in light of the following factor: in 2023 the integration of Mandarin in Sakha was conducted on an experimental basis, and in one year the study of Mandarin skyrocketed throughout the secondary education system of the Republic. Perhaps, even more crucially, the Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University (NEFU) and Changchun University of Science and Technology (Changchun, Jilin Province) sought to expand their strategic cooperation with Sakha which resulted in the emergence of the joint Sakha- Changchun Technological University. Moreover, China chose to locate the main campus on Chinese territory (Longjing) for the purpose of bringing students from Sakha directly to China for their education. Such a development would widely expose these students to Chinese culture and political influence.

Third, leisure and entertainment. After February 2022 there was a dramatic increase in the popularity of China as a tourist destination and as a source of inbound tourism. Russian sources reported two critical trends. On the one hand, in terms of outbound tourism, China has become the most desirable destination for the inhabitants of Sakha, beating such traditionally popular destinations as Turkey and Thailand. At the same time, the inbound tourism from China to Sakha grew by 50 percent. While the overall number of Chinese tourists remains meagre (official outlets reported only 223 Chinese nationals visiting the Republic in 2024), the overall dynamic appears impressive. Likely, this number is going to increase due to the growing interest (was explicitly articulated in 2025) among Chinese entertainment and movie-producing companies in launching production on the territory of Sakha.

Conclusion

The image of Chinese cooperation with Sakha in the post-2022 period presents one big optical illusion. On the surface, the scope of bilateral trade has grown – although, based on local sources, the monetary amount of bilateral trade, having soared first, is now declining – and other realms of cooperation are booming as well. Thus, one could erroneously view Sakha as becoming a sort of land“bridge” – just as Moscow wants it to look like – between Russia and China. A far deeper analysis, however, indicates that China is deliberately avoiding engagement in strategic cooperation with Moscow by purposefully limiting its bilateral trade to simple import-export ties, which transforms Sakha into a Chinese raw material appendage. Meanwhile, the Republic is increasingly falling under Chinese cultural influence. Given rapidly spreading poverty and mounting military losses in the Russo-Ukrainian war these trends could eventually translate into a far greater long-term strategic concern for Moscow.

Notes.

[1] Analysis of Russian sources reveals a notable discrepancy. While the overall volume of trade between Sakha and Chinese provinces has indeed increased since 2022, local sources highlight an interesting trend: in 2023, bilateral trade amounted to $2.5 billion, yet in 2024 Russian sources hailed an “impressive $1.8 billion.” Although still substantial, this figure actually represents a significant decline in trade value.

[2] The term “Mongolian race” is currently considered to be obsolete.

Thank you for your support! Please remember that The Saratoga Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization. Your donations are fully tax-deductible. If you seek to support The Saratoga Foundation, you can donate by clicking on the PayPal link below! Alternatively, you can also choose to subscribe to our website to support our work.

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=XFCZDX6YVTVKA

Thanks for reading! This post is public, so feel free to share it.

Fascinating read, thank you. Look forward to reading more on the subject!