Prometheanism, a program developed by Poland and numerous non-Russian emigrations from the USSR in the interwar period, is now the all but declared centerpiece of Kyiv’s push to weaken Russia and transform the remains into a democratic country capable of living in peace with its neighbors. The parallels are so complete that it is entirely reasonable to say that Kyiv has adopted Prometheanism as its guiding principle in dealing with Russia. Nor surprisingly, official Moscow is both worried about and outraged by such a possibility, yet another reason why Prometheanism deserves far closer attention in the West than it has received.

There are two reasons why the original Promethean period has not yet received book-length treatment in English, and an additional reason why the neo-Prometheanism of the last several years in Poland, Ukraine and several other countries has not either. During the existence of the Promethean movement in the 1920s and changes, both in Polish politics and the international situation in Europe in the 1930s passed through a complicated series of changes, changes which meant that sometimes Prometheanism had the official support of the Polish government and sometimes lacked that but was supported informally by officials in the Polish army and intelligence services.

Over the same period, more than a dozen different non-Russian immigrants who were involved also went through numerous transformations; and because all of these groups used different languages, the task of tracking their developments is clearly beyond the ability of any one investigator.

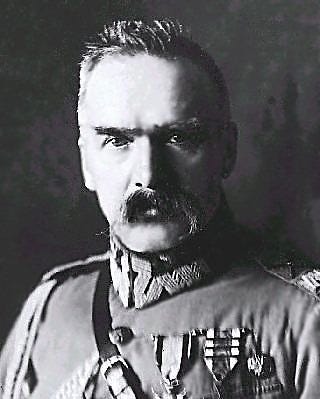

But the basic principles of Prometheanism never changed – support for the right of non-Russians within the Russian state to become independent and the need for them to cooperate and have the support of friendly foreign countries. Those principles were first laid down by Józef Piłsudski in 1904 in a memorandum to the Japanese government in which the future ruler of Poland argued that in fighting Russia, it was critically important that the non-Russians be supported, encouraged to unite and work closely with foreign countries so as to weaken Russia and open the way for that country to become free and democratic and capable of living in peace with its neighbors rather than seeking to reabsorb them into an empire.

Although Prometheanism as a distinctly Polish project died with the onset of World War II, these ideas informed many projects during the Cold War including the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN) and the Captive Nations Week resolution; and they have gained new influence since the coming to power of Vladimir Putin and his aggressive reassertion of Russia’s right to be an empire.

Analysts in Poland, Georgia, and Ukraine in the last several years all have pointed to the need for non-Russians to have the right to exercise self-determination and become independent, for them to cooperate rather than work in isolation one from another, and for them to have the support of outside governments. These ideas have been picked up by various émigré groups, but their most important converts were members of the Ukrainian government since Putin began his effort to dominate Ukraine and absorb part or all of it into a revived Russian empire.

Among the actions the Ukrainian government has taken that reflect its commitment to the ideals of Prometheanism are its support for Ukrainian communities inside the Russian Federation, the so-called “wedges;” support for the aspirations of various ethnic minorities most prominently the Chechens and the Circassians by the Verkhovna Rada’s recognition of the former as a temporarily occupied land and of the latter’s call for concluding that Russia’s expulsion of the Circassians was an act of genocide; its work with other countries in the region to promote such ideas; and its support for the opening of the Promethean Center for Security Research in Lviv. Not surprisingly, Russian officials and commentators have attacked all these actions as threats to Russian national security and demanded that they be reversed.

Happily, Ukraine has not agreed and continues to follow its Promethean line even though it has not openly declared that that is what it is about lest it make things even more difficult for its allies within the current borders of the Russian Federation. But just as the original Prometheanism kept hope alive for many peoples in the USSR, so too Ukraine’s Prometheanism is doing the same thing – and also like its predecessor is likely to have an even greater impact than that however often and viciously Russians attack it.

For background on the original Promethean movement that makes all this clear, see among others the following articles and books in which it has been most usefully discussed:

· Edmund Charaszkiewicz, Zbiór dokumentów ppłk. Edmunda Charaszkiewicza, (Biblioteka Centrum Dokumentacji Czynu Niepodległościowego, vol. 9 (Cracow, 2000)

· Etienne Copeaux, “Le mouvement prométhéen,” Cahiers d'études sur la Méditerranée orientale et le monde turco-iranien, 16 (1993): 9–45.

· Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, Intermarium: The Land between the Black and Baltic Seas (New Brunswick, NJ, 2012)

· Sergiusz Mikulicz, Prometeizm w polityce II Rzeczypospolitej (Warsaw, 1971)

· Zaur Gasimov, "Zwischen Freiheitstopoi und Antikommunismus: Ordnungsentwürfe für Europa im Spiegel der polnischen Zeitung Przymierze", Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte, 12 (2011): 207-222

· Zaur Gasimov, "Der Antikommunismus in Polen im Spiegel der Vierteljahresschrift Wschód 1930–1939," Jahrbuch für Historische Kommunismusforschung, 2011, 15–30.

· Richard Woytak, "The Promethean Movement in Interwar Poland," East European Quarterly, 18: 3 (September 1984): 273– 278

Thank you for your support! Please remember that The Saratoga Foundation is a non profit 501(c)(3) organization. Your donations are fully tax-deductible. If you seek to support The Saratoga Foundation you can make a one-time donation by clicking on the PayPal link below!

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=XFCZDX6YVTVKA